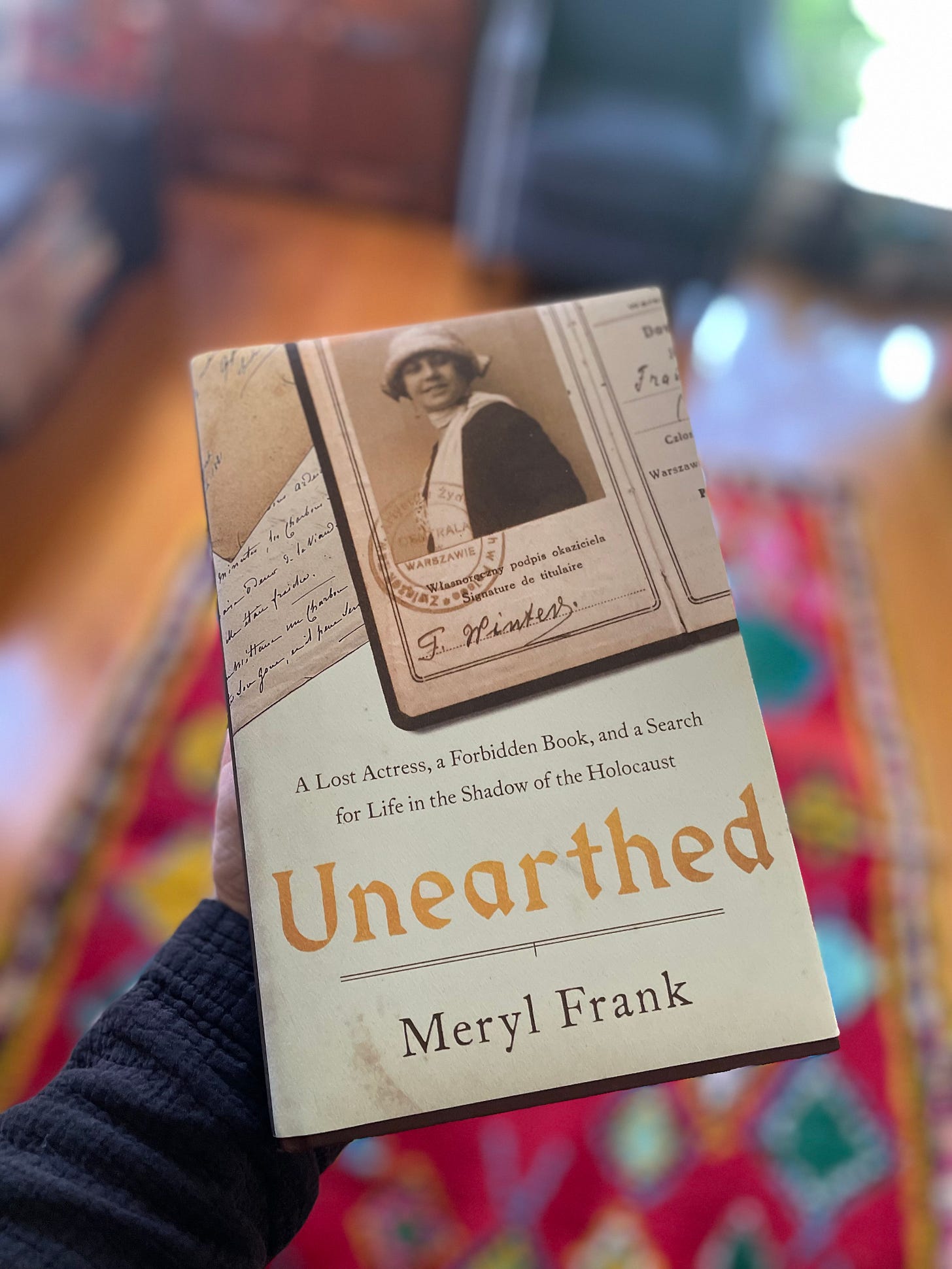

The following is a guest post written by my cousin, Meryl Frank, with an excerpt from her new book, UNEARTHED: A Lost Actress, a Forbidden Book, and a search for Life in the Shadow of the Holocaust.

I don’t remember a time when I was not aware of the Holocaust, a time when I was not consumed by it, a time when it was not lodged in my consciousness or deep in my bone marrow. Though I grew up in an average American household in New Jersey, where there was intentionally little talk of the past, I understood from a young age that our history was mired in loss.

My parents themselves were not Holocaust survivors, but much of my mother’s extended family had been murdered and disappeared by the Nazis. As a small child, I would dig deep into the recesses of my parents’ TV cabinet and unearth a worn manila envelope full of photographs of these missing relatives, then pore over sepia-tinted pictures mounted on cardstock while Bewitched played in the background. Many of the portraits were formal, reflecting the bourgeois proprieties of their prewar life, but one person always seemed to stand out in living color: My cousin, a famous actress of the time named Franya Winter, was featured mugging for the camera in wild costumes, evoking something riotous, playful, even sexy. I was instantly compelled by her. And that interest was only enhanced by the fact that her death was a mystery.

Recognizing my attachment to my family’s memory, my aunt Mollie eventually entrusted me with a Yiddish book called, Twenty-One and One, which described the lives and deaths of actors who died in the Vilna Ghetto–including Franya. “Keep it and pass it onto your children,” my aunt commanded. “But don’t read it.” She never said why, but there was clearly something she wanted to keep secret.

Thus began my search for knowledge beyond the forbidden book. I would keep my deathbed promise to my aunt, while unearthing answers to the questions that had plagued me my entire life, honoring my family in their death. That quest that would take me across continents to meet survivors, search archives, and wander the streets my relatives once tread. And, at one point, it took me to Iowa to a writer’s workshop, where I began to consider what my eventual book, Unearthed (which came out on April 11th), might look like–a workshop where I would wind up unexpectedly uncovering the truth about what happened to Franya.

I was constantly checking and rechecking sources, which changed rapidly

as more documents were shared online. Each day I sat down in front of my computer, hoping for that next piece of the puzzle to fall into place.

Then finally in early 2017, my repeated Google searches for Franya, under every conceivable spelling of her first and last names, yielded a promising new hit: the testimonial narrative of one of her fellow actresses, Dora Rubina. She had participated in the Yiddish ghetto theater, and survived the ghetto in Vilna and many other misfortunes, before being liberated by the Soviet army at a Nazi transit camp in northern Poland in March 1945.

Bracing myself for new revelations, I clicked through to the link titled “The Path of Suffering of Jewish Actors.” Chills ran through me. Rubina’s experience was the closest I had come to one that mirrored Franya’s, as she’d been both a peer and a fellow performer in Vilna. They’d existed in the same sphere with the same general set of circumstances. The testimony had originally been taken for the Białystok Ghetto Underground Archives, most likely because Rubina was born in Białystok, and was only now cataloged in Yad Vashem’s collections, making it accessible to me. Six pages were available for download, but in Yiddish only, so I couldn’t read them right away and had to send them to a translator at YIVO. What I could read, though, was a detailed accompanying English summary of Rubina’s account, which included a reference—in list form—that stopped me in my tracks:

. . . resistance to the Germans by Franja Winter, the actress; murder of the actress by the Germans.

My heart raced as I absorbed what I’d read: resistance, murder. Here, apparently, was another source, beyond Twenty-One and One, that might tell me what had happened. Here was the confirmation that I had been seeking. Was this my opportunity to learn the truth and still stay true to my aunt’s wishes? Had I gotten there myself? I reread the abbreviated text, finding the word “resistance” reassuring. It seemed to confirm what I’d wanted to believe about Franya all along—she was strong, a fighter, loyal to our side.

I was able to make arrangements to have the testimony translated right away, though I knew it would not be immediate. I reexamined the summary countless times, noting that Rubina must have met up with Franya in late 1939 or early 1940, after she fled Nazi-occupied Warsaw. Vilna was still free of German control then. The two of them had been in a revue ensemble together, then in the Yiddish state theater established after the Soviet Union annexed Lithuania in June 1940. Clearly, they had known each other well. Maybe they had even been friends.

It was clear from the summary that Rubina’s experience even after Vilna had been harrowing. The text referenced escape, recapture, the arrest of her husband by the Gestapo, deportation, forced labor, a “death march” marked by terrible hunger and disease, and, finally, liberation. Eventually, she made her way to California, where she passed away in 1983. Only a hair’s breadth separated the experience of those who died at the hands of the Nazis from those who survived.

In the meantime, I had decided to take on another endeavor as well. Years of research, plus countless stories about the sanctity of books and the written word in Jewish culture, had made me want to try writing about my heritage. This felt like the ultimate fulfillment of my role as the memorial candle for my family—creating one place for all of the information and realization I had amassed over the years. At this point I was working as a consultant, enacting women’s leadership training, and could make my own hours. So I surprised my husband at dinner one night by announcing that I had signed up for a two-week intensive course at the University of Iowa’s Summer Writers’ Festival, “The Novelist’s Tools: Fiction and Narrative Nonfiction.”

I was sitting alone on the college quad, surrounded by students hanging out on the grass, when I received an email with the full translation of Rubina’s testimony. At first I was afraid to open the email. If I’m honest, though I had been anticipating reading it for weeks, arguably for years, a kind of emotional paralysis came over me. I was confronted with a dilemma: I was far from home and the people I loved. The years of hard work and discovery had rendered me less emotionally protected than when I started. I was open to whatever might come. In my gut, I knew I would feel this pain to my core, no matter how strong I wanted to be. Reading Dora Rubina’s account was going to be taxing, and now I had to face it alone.

Again I remembered Mollie’s admonition and worried that there might be something truly frightening about the story I might be better off not knowing. Then I had an unorthodox idea: I would ask my professor if I could read the testimony aloud in class. All but one of my classmates were white Americans from the Midwest, the sole exception being a doctor who now lived in New Jersey but was born and raised in the Midwest. As we each read aloud our writing assignments, it became clear to me that as a Jew, I was an anomaly, exotic, quite different from my classmates. One was writing about her experience as a rancher, and another was writing about his child- hood in rural Iowa, and yet another about a long-lost love affair, far removed from the story I was seeking to tell. I knew from our shared writing exercises that they knew almost nothing about Judaism and even less about the tragedy of the Holocaust. Suddenly, I saw it as a challenge, even an obligation, to bring them into the experience with me. The professor was more than amenable to the idea.

I found myself reading Rubina’s testimony to a room of people I barely knew at the very next class meeting. She recounted the “horrifying days” that followed the Nazis’ arrival in Vilna; about the men snatched from their houses, never to be seen again; about the establishment of the ghetto; about a “purge” of people without work permits; about the devastation in the acting community as news reached them that one performer after another was dead.

Then she turned her focus to Franya. I looked up from my laptop at my classmates, who sat around the rectangular wooden table in the windowed room, eyes glued to me. My teacher nodded to me in patient encouragement. Inhaling, I gathered my strength and continued reading.

Franya Winter, Dora explained, did not receive a yellow work permit. Knowing that this was tantamount to a death sentence, she hatched a plan and escaped the ghetto with a group of workers. According to Rubina, Franya then sought help from a Christian acquaintance with whom she spent a few days, until the woman forced her to surrender payment in the form of “her worthwhile things, such as jewelry and gold . . . and chased Franja into the street.” Pausing, I tried to imagine such a betrayal, and there was anger, but also a kind of pride. Franya had refused to give up her treasured jewelry, after months of proclamations demanding that Jews turn in all their valuables. It was a small act of rebellion, but it showed her strength in the face of the most repugnant human behavior. And of course our family had always seen our pieces of jewelry as talismans, more meaningful than just a pretty bauble.

As the story progressed, Franya was captured in Ashmyany, just as I had come to suspect, in 1941. Dread welled up inside me as I forced my eyes back to the screen.

“Franja Winter, just like the rest of us, did not want to die,” I read, voice shaky. “She struggled with her last abilities . . .”

My brain registered what my eyes were reading before my lips could form the words, and, in that split second, I stopped and slammed my laptop shut. Words eluded me. I sat upright, jaw clenched, unable to move, breathing deeply in an attempt to keep my composure. The room seemed to morph around me, suddenly unstable. And in that classroom with near strangers, I broke down. I could not stop my tears from flowing.

My classmates said nothing.

“You don’t have to share any more than feels comfortable,” the teacher said gently.

But I was determined to continue. I owed it to Franya. Her story, no matter how gruesome, needed to be told. Wasn’t that why I had started this whole quest? Wasn’t that the ultimate goal?

I reopened my laptop, exhaled a stuttered breath, and searched for the strength to form the final words.

As I reached the conclusion, the classroom fell into a hush again.

“And that is how the actress, Franja Winter, who all the years helped spin the thread of culture and artistry, ended life.”

People were quietly sobbing.

After a long silence an older man, a church deacon from rural Iowa, said, “The terrible thing is that, in thirty years, no one will know that this happened.”

My response was swift and unforgiving. “It is still happening,” I said. “Every day…”

Meryl Frank is the author of Unearthed: A Lost Actress, a Forbidden Book and a Search for Life in the Shadow of the Holocaust. She is the former US Ambassador to the UN Commission on the Status of Women and the former mayor of Highland Park, NJ.

This is incredible. I am going to order two copies: One for me and one for one of my best friends whose grandparents met in a camp and survived, making it to America. Her Papa Jack just turned 100. I also love the concept of being the Memorial Candle for a family. I am not Jewish, but I am the researcher and scribe of my family's history too. I love that there is a name for this role. Thank you for sharing your cousin's work. xoxo