what is consent to a ghost

a critique (and vindication) on my own gaze and an invitation for you to center yours

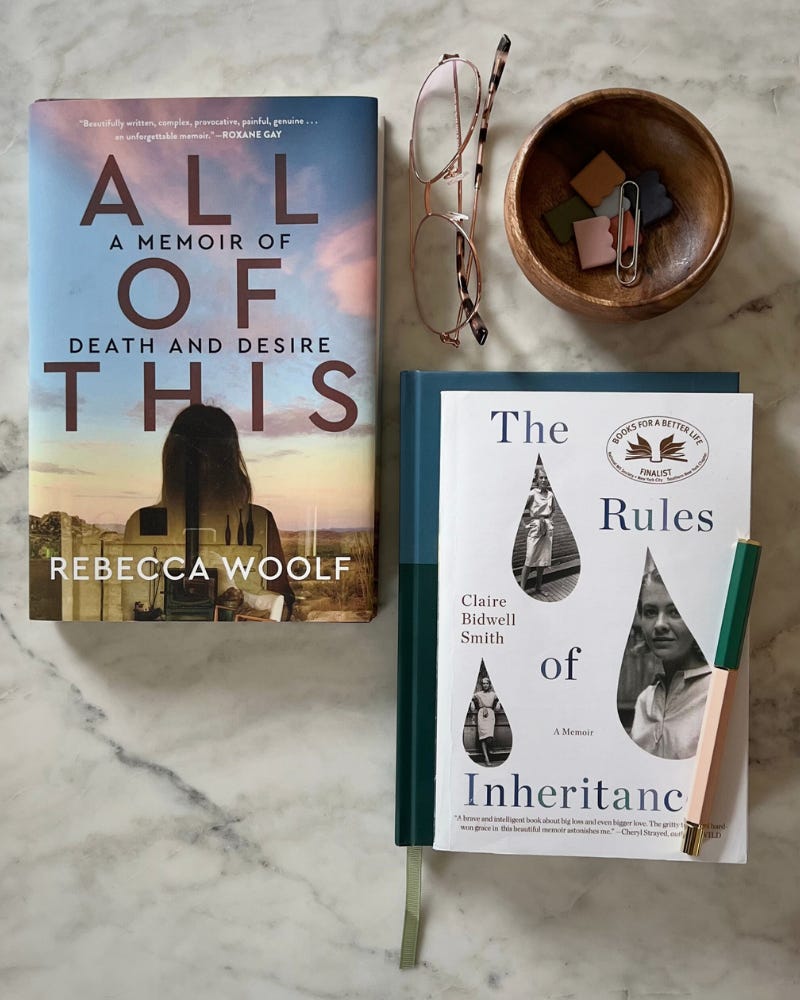

The Living Gaze*, the grief writing workshop I have hosted with beloved friend, therapist and fellow author, Claire Bidwell Smith for almost three years is back this fall and currently open for enrollment. Whether you’re interested in writing a memoir or are looking to write therapeutically through your grief, our course is designed to offer you safety, solidarity and support in your grief experience, regardless of its shape. For more information about our six-week course (October 1 - November 5th) go here.

*I wanted to share the essay that inspired the name of our course, The Living Gaze.

In the weeks after my memoir, All of This came out, I published the following critique/vindication on my gaze in the hopes it would stir readers to devote the necessary energy to do the same for their own.

Since the following essay was published, I have worked with dozens of writers on their grief memoirs and personal essays — both with Claire in our workshop and during one-on-one meets, with the goal, above all else, is to validate EVERY AUTHOR’S GAZE, specifically when it comes to their grief — an experience that is so often withheld or hidden behind its expected performance.

It is an act of service both to the self and to the reader to be real both on and off the page. It is also extremely difficult to accept the complex humanity of both the self as a writer and the dead through one’s grief. But when you can and do… paradigms shift, in our brains and beyond.

All of this to say, bravery is contagious. Especially when stories are shared and received in the same room.

The following was first published in December of 2022.

One of the last big fights we had before he died was about a corpse. My husband, Hal, was months away from being diagnosed with stage four pancreatic cancer—a cancer he didn’t know he had until it was too late—but before that, before we knew he was dying, when it was just two unhappily married people barely speaking to each other, he had become obsessed with the story of Carl Tanzler and his one-sided love affair with his patient, Maria Elena Milagro de Hoyas.

The story goes like this: Tanzler had fallen in love with one of his patients – a young woman dying of tuberculosis who he was unable to save—a woman he had fallen deeply in love with – one-sidedly. Following her death, he paid for her burial and eventually stole her corpse from its mausoleum and spent several years living with it. Fucking it, maybe. No one knows for sure, but what we do know is that he had a years-long one-sided non-consensual relationship with her dead body that lasted up until Elena’s horrified family discovered that Tanzler had stolen, and was living with her decaying corpse.

Hal wanted to option the story – develop it for film. His working title was A Grave Affair. When he first mentioned it to me in passing, I didn’t think he was serious, but when he brought it up a second time, explaining he had already reached out to several people and was hoping to meet with someone who already was working on a musical adaptation, I lost it. This was not the first time he was invested in a love story with an exploitative power dynamic and while I had reluctantly supported his side projects in the past, even when they stood for everything I was railing against with mine, I was no longer masking my disgust.

He became obsessed with the story, the fact that even after death, a man’s undying love for a woman was all that mattered. Never mind that she didn’t love him back. That she was a corpse, dead and rotting in his arms.

In his words, it was a deranged and unusual love story.

“This isn’t a love story. This is a story about obsession and a dead woman who had no autonomy. This is about a man who kidnapped a woman’s dead body. Decided she belonged to him. STOLE her from her resting place. She probably didn’t even like him. He probably gave her the creeps. HE WAS HER DOCTOR WTF.”

Hal did not see the story as one of obsession and male dominance, but one of love. He felt it was one of the most fascinating, albeit macabre, love stories of our time and that it deserved to be retold. That it was weird and fucked up, but represented something human and carnal in all of us: that sometimes we cannot – are unable to – let go.

I was horrified that he thought there was anything fascinating about this story. He thought I was overreacting. I believed he was so fundamentally wrong to think this was a love story, but more than that, I compared it to my own. To feeling corpse-like in my own marriage. To going through the motions as his wife, feeling dead inside. What about how I felt? What I thought? Did it ever matter? I never doubted that he loved me but also … he loved me in his own way, never mine.

I had been married to this man for nearly thirteen years. And THIS was the love story he wanted to tell? This was what resonated with him? A man’s undying love for … a woman who would never love him back? A woman he could ONLY have in death, who he had dug up for his own pleasure, amusement, and joy? A woman whose feelings didn’t matter let alone exist.

His argument was that she was dead so what difference did it make. Tanzler wasn’t hurting anyone, least of all, her. And besides, we do crazy things for love.

One could say it was a similar argument I would find myself using to justify writing a memoir that included details about my marriage with a man who was no longer alive. It’s just that the love was for me this time.

Certain people believed I was also being self-serving in writing about my experience. That by writing my book I was digging up the corpse of my beloved – a man with whom I, too, had a complicated love story.

I don’t think anyone is wrong to feel that way. But I also believe we have normalized love stories being things that are other than complicated — a far more harmful thing.

In her memoir Why Be Happy When You Could be Normal, Jeanette Winterson writes,

“…unhappy families are conspiracies of silence. The one who breaks the silence is never forgiven. He or she has to learn to forgive him or herself.”

And then, of course, there’s the Sinead O’Connor lyric (Black Boys on Mopeds)

“To say what you feel is to dig your own grave.”

Truth telling gets us into trouble. Women, especially. Our silence is what makes us lovable. Our loyalty is what makes us safe. A dangerous woman has historically been a thing to villainize. Criticize. Shame. But a quiet one? A compliant one? A … dead one? It makes perfect sense that to many men, a corpse would make the perfect wife.

The truth is, it took my husband dying for me to write honestly about my experience, not only as his partner but as me. I had spent so many years lying to both of us, out of fear but also out of a need to protect both of us — our children — the family portraits on the fridge. No one wants to be an unhappy wife but women, so good at faking it, can go entire lifetimes without anyone ever having to know.

Beyond that, so many of us are afraid of the people we love, and it wasn’t until my husband died that I realized I no longer loved anyone in my life who I was also afraid of.

No one scared me anymore.

This is such a liberating concept and one I believe to be anomalous considering the conversations I have had through the years, mainly with women, fellow essayists, memoirists and writers of first-person non-fiction who feel they cannot write honestly about their complicated love stories.

When a writer is afraid of the people she loves – afraid of their judgment, their shame, their lack of support – she must make the choice to either tell her truth or make the people she loves feel comfortable. There is no other way.

Over the past few months, I have spoken at several writers’ groups and memoir workshops and everyone asks me the same question. How do you tell your story without hurting people?

And the answer is always the same. You can’t.

I touched on this briefly before and I intend to go into it deeper in future essays but a locked diary has never protected the writer so much as it protects those who have hurt her. That includes the loud and oft intimidating voices inside herself that for years have shamed her into compliance.

Even the loudest among us know exactly when to fall silent. It is a practice. And then, hopefully, eventually, an unlearning.

In the end, people will always make your personal story their personal affront. I have spent twenty-five years doing this work and have known all along that there is as much risk as there is reward. That for all the deep “I see you” love, there is hatred and a never-ending stream of judgment.

It’s why I love writers so much— memoirists — those who are willing to be human, vulnerable. Disliked. Fucked up. Free. I want my writers naked. With nothing but shoes on in case they have to make a run for it. I do not seek heroes in the people I read or write or raise or love. I seek humans.

In Melissa Febos’ Body Work (pgs 26-27) she writes, “Almost everything I’ve ever written started with a secret, with the fear that my subject was unspeakable. Without exception, writing about these subjects has not only freed me from that fear but from the subjects themselves, and from the bondage of believing I might be alone in them. What I have also observed is that avoiding a secret subject can be its own form of bondage. To William H Gass’s argument, ‘To have written an autobiography is already to have made yourself a monster,’ I say that refusing to write your story can make you into a monster. Or perhaps more accurately, we are already monsters. And to deny the monstrous is to deny its beauty, its meaning, its necessary devastation.”

Still, I recognize and find myself sitting with the same criticism of my work. I made a choice to write a book that my husband did not word-for-word sign off on – the only time I have ever written something about him that I didn’t give him final cut on. For years I wrote about our marriage, but only after giving him my work to read first to make sure he was comfortable with what I publicly shared. Every writer I know has done this, put their partners first. Often at the expense, not only of their work but of their truth. I know a lot of writers doing this now. I read them and know. Because if you know… you know.

Arguably, what I did to Hal was the same thing Tanzler did to his corpse-bride. I dug him up and brought him back to life in my image. I replaced his skin with silk. Put my need to tell my story first. Instead of allowing him to rest in peace, I went into the cemetery at night and spent a year with him propped up on the foot of my bed so that I could tell a story from one side. Claimed love as the culprit, but the love in my heart was for me.

***

My husband has now been dead for more than four years. And thousands will have read my book having never known him. And many will believe that I, too, have excavated his body in order to fulfill my own need to prove the livelihood of mine. And they will be right. Their criticism is as valid as my decision to tell my truth.

Every writer chooses herself if she is going to write honestly. There is no other way. I have spent my entire life writing stories about myself as I relate to other people – beginning in high school when I wrote about the boys who broke my heart as a teenager for Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul.

More recently, I have wondered why anyone has willfully dated me, knowing that they might end up on a page at some point, because everyone who is close to me inevitably has. Perhaps they knew I would protect them, that I would make myself the butt of the joke — which I have always done. Even in those early days, I was always hardest on myself.

I think of all the teenage girls — me included — who spent their formative adolescent years with reputations rooted in jealousy, lies, judgement. Had to wake up and show up to school every day with our names sharpied across the backdoors of bathrooms attached to words like slut, whore… How for so many women I know, taking back our stories was never about revenge but survival. Owning the parts of us that were scrutinized, shamed… saying, oh you think I’m too much? Just wait.

Last year I fell in love with a man who made it very clear from the beginning that he didn’t want me writing about us – or him. I understood, of course, and never made mention of him or us publicly. And then, days after reading my book, he broke up with me. What I had written about my life—about my marriage, sex life, me—gave him pause. And I realized (albeit agonizingly) that I had, once again, chosen myself. That by writing this book, I made the decision to end future relationships before they even began. That it would take a certain kind of partner to be comfortable, not just with my past, but with our future. That any day they—or our love—could die and I could write about them, too.

I have always made my living writing about my life, which means it will always be a risk to love me. And in understanding that, I must honor the feelings of those who feel they must leave me in order to protect themselves. Just as I have chosen to honor my feelings by making the choices I have made in my work. It has always been the paradox of truth telling — that what sets us free will also alienate us. That anyone who writes honestly about her life is, in a sense, digging up the bodies of her beloveds, dancing with their deteriorated flesh. Making words out of the bones.

Before I started this essay, while looking for some old paperwork on his desktop, I found Hal’s A GRAVE AFFAIR folder. His correspondences were thrilling. His passion palpable. His need to tell this story was suddenly relatable to me in a way it wasn’t when he first tried to tell me about it. And while he never gave me full consent to write about all of the things I wrote about in my book, he did tell me, on his death bed, that I had to write our story, perhaps for the same reason he wanted so desperately to tell Tanzler’s.

Because he recognized that love is not always selfless—that it is often grotesque and inhumane. That humans are complicated animals and acknowledging that without judgment is nearly impossible. That we are drawn to stories and to telling them for reasons many will never understand.

That doesn’t mean we all deserve to be forgiven, immortalized, let go … but to hold each other against the light, as unfiltered, nuanced human beings is not unloving and to say so is to assume a false identity. None of us are heroes. No matter how hard we want to write ourselves (and each other) into such molds.

“…And to deny the monstrous is to deny its beauty, its meaning, its necessary devastation...”

Which makes our need to tell certain stories arguably more interesting than the stories themselves—our willingness to put our own necks on critical chopping blocks. Because even though my book made some people uncomfortable, I have never regretted a word, in the same way my frustration with many of Hal’s projects never kept him from pursuing them. That for all our differences, we were both similarly unencumbered by judgment. Because in the end we both believed that unpopular love stories were worth telling, regardless of who we might lose or disappoint in the process.

Including each other.

Rebecca, I loved this essay when I first read it and even more now.

The Living Gaze (parts I and II) were quite possibly the best thing that I did after Liz' death. If anyone is interested in brilliant workshop writing, while exploring the shit that is collectively referred to as "grief," I could not recommend the course more. P.S. You get to meet an incredible group of writers, many of whom are on this platform, and somehow call them by name as if you are "friends".

Damnit Rebecca, you're such a beautiful and profound writer. Every paragraph you write tells so much and I dont know anyone who has found such truth from a terrible journey like you've been through. Please write more and keep sharing.