Yesterday, upon hearing about Heather’s death, I immediately went through our old texts. I was looking for her final words — a sort of death statement — something I have always done in the wake of a sudden loss. I have always, every time, found what I was looking for — especially from writers. The good ones, if we choose to pay attention, are forever writing their own eulogies. I think in a way, all of us write knowing that someday — if we do it well — people will come back to our words after we die and find us there. And Heather was a good writer. She was a BRILLIANT writer. Hers was the kind of voice that pulled so many of us into a brand-new-baby Internet only to keep us there indefinitely, riveted by the hilarious and heartbreaking humanness of her stories.

Hers was a voice that made us want to do what she was doing.

Made us think that we could.

I think about death a lot — like all the time — and lately — with my oldest leaving for college in the fall — death has felt less literal to me, more of a bend in time. A shape-shift. A tarot card.

I was moments away from publishing a post about anticipatory grief yesterday morning when I got the call that Heather died. I almost posted my piece anyway because it felt, in a way, related. (When I pub it you’ll see what I mean.) But I didn’t because I knew I wanted to write this even as I’ve struggled mightily — overwhelmed with grief, not only for Heather but for an uncredited era that dies with her.

Every woman who writes words on the Internet is walking a path that Dooce/Heather Armstrong helped forge. In the space of Mother Writers on the Internet, she was The First. Do you know how hard it is to go first? There is a reason why no one wants to go first. (I hate going first.)

Lyz Lenz wrote in the Washington Post yesterday, “It takes a difficult woman to be the first to do difficult things. Heather would have been the first to acknowledge, loudly, how difficult she could be.”

And she’s right.

I first started blogging in 2002 on a blog I called The Pointy Toe Shoe Factory. My friend Dana Robinson built my website and taught me basic HTML. I had a few links on my blogroll, Dooce at the top, and I was there, reading her words from the get. Before her first child was born.

We wouldn’t meet until years later or become friends until 2008 when we appeared on a web series called Momversation (the above photo was taken by our producer, Rob) but I read her religiously through my pregnancy with Archer and in the months and years that followed.

PTSF turned into Girl’s Gone Child when my son was born in 2005. I knew absolutely no parents then. Just the ones I followed on the Internet. I was young and raw and clueless and she made that seem okay.

The first time we met in person, I was starstruck. I knew her through her writing. That’s what it felt like, anyway.

When we spend years on the receiving end of someone’s stories, is it not impossible to fall in love with them? Especially with those willing to be vulnerable? Human? Flawed? It’s impossible for me. I fell in love with everyone in those days, especially her.

What I always loved about Heather was what I hoped I would achieve for myself. The kind of honesty that people are afraid of because we’re not — as women — and especially not as mothers — allowed to say THAT SHIT OUT LOUD.

As a new mother, I was hungry for the OUT LOUD in the most insatiable way. I still am. Girl’s Gone Child would be eighteen this year. The same age my son turns in a little over a week. A generation come and gone. A lifetime. And there is grief there, too. In recognizing the babies we all witnessed get born are now adults. All those birth stories, remember them? Yeah, well. Those babies can vote now.

Elizabeth Angell, EOC of Romper wrote this about Heather, yesterday, in an essay paying her respects:

In my IG post yesterday, hundreds of people commented with the same words.

“Because of Heather I was able to write honestly about my experience.”

“Because of Heather I was able to get through those early years of motherhood…”

“Because of Heather I was able to feel seen.”

“… was unafraid of becoming a mother.”

“… of being messy.”

“… of being real.”

“Because of Heather, I survived…. “

I can’t think of a more honorable legacy than that.

The Internet is so many things but mostly it is generous and cruel in equal part. The same people who tell you they love you will tell you they hate you two days later. Will tell you to die. Will show up at your house and think you’re friends. Heather knew this more than anyone, perhaps, at that time and for years fought back. I don’t think it’s possible to criticize her for that without knowing how HARD that is to shoulder. And I don’t know how anyone with the mental capacity for that much hate would be able to function properly, let alone someone vocal about her depression. But she did… for years. Until she didn’t.

I will never understand what compels the underbelly of the Internet to attack ANYONE let alone those who share vulnerably about their mental health struggles but I do know that the brave will always speak and the weak will always silence and that the Internet keeps its lights on by catering equally to both.

ED: I made the mistake of reading one of the comments sections in one of the recent NYT pieces on Heather and was struck over and over by those who dismiss the life-changing, culture-shaping power of storytelling. Humans of all genders — have been telling our stories since the beginning of time. Not to seek validation but to encourage the truth to exist in a public forum. And the Internet just happens to be another way to share it. A different kind of camp fire. A cave wall with wider reach. To blatantly overlook the lives changed by personal essays and to infantize thousands if not millions of women who came to life through writing about our own is nothing new, of course, but its proof that the work continues to be as culturally urgent as it is personally dangerous.

Sharing personal stories has ALWAYS been as integral to our survival as shelter. Especially for the women who have been force-fed abusive narratives from the books of patriarchy. So many women — mothers — friends of mine — were able to deconstruct the lives that were harming them and rebuild new paradigms in their place for themselves AND THEIR CHILDREN — BECAUSE of the stories they found here.

In the words of moms.

On the Internet.

What people keep missing (over and over. and over) when we talk about those early days of blogging is this: no one was there for the fame. Or the attention. We were there because we were writers. And writers fucking write.

I have written about this here before, but it bears repeating: there is a reason young girls are given locked diaries. We have been told our whole lives to keep our truths to ourselves out of SAFETY. Safety for ourselves. For our families. But our secret lives do not keep us safe, they only enable the same lie we have been told for centuries. That our stories are not the ones that matter.

But they do. And because of Heather Armstrong’s willingness to be honest and raw and vulnerable and messy, an entire generation of us believed we could, too.

An entire generation who have now raised an entire generation. A generation unafraid to challenge the bullshit binaries and refuse the same agenda we did when we sat down at our computers to write OUR stories. A generation that claps back in a way WE NEVER DID (or felt we could) at their age. (I certainly didn’t.)

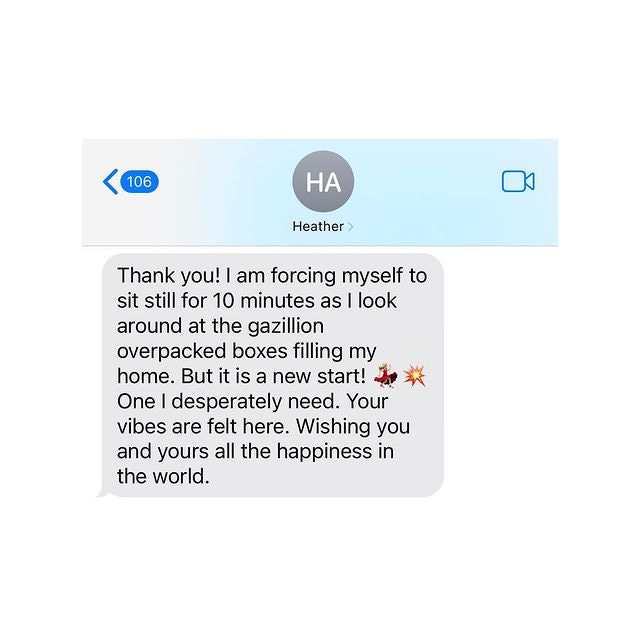

The following is the text I screengrabbed and posted on Instagram yesterday. The one I was talking about earlier. A found poem in text messages.

It reminded me of those early days of blogging. When we all felt overwhelmed by boxes but forced ourselves to sit down and write anyway. When there was real love between author and audience.

When we wrote to FEEL SEEN and to SEE EACH OTHER BACK.

There have been very few days in the last twenty years when I have not sat down and written something to eventually publish on the Internet.

Every word I write has a history that will forever be traced back to those early days of blogging with Heather Armstrong at the start. And fuck your labels, no, I will not use that word.

Because we were always more than that.

She was always more than that.

And that’s why we couldn’t stop reading. It’s why our collective grief is so much more than what any of us can articulate here or on Instagram or anywhere else. But it is a privilege to have the ability to string words together in an attempt to try.

And I so appreciate everything I have read so far that has. From Lyz Lenz to Elizabeth Angell, to EJ Dickson and Lisa Belkin… And all of the posts I’ve read these last two days from Heather’s old friends and colleagues. From you.

She deserves our best attempt at honoring her legacy. Especially in the place she helped build.

Rest easy, Heather.

Thank you, Dooce.

Your vibes will be felt here forever.

Heartbreaking humanness, oh wow, yes. This is why, despite being single and childless, I found solace in dooce and GGC in my early adulthood. You both made me feel infinitely less alone in my humanity, in the raw nerve of my existence, and gave me room to believe big feelings meant big possibility. Thank you to you both.

"What people keep missing (over and over. and over) when we talk about those early days of blogging is this: no one was there for the fame. Or the attention. We were there because we were writers. And writers fucking write."

This. THIS AND THIS AND THIS AND THIS AND THIS.

This is what I loved about those days and this is what has filled my entire heart about what is happening here on Substack.

I wouldn't be the writer I am without Heather. I wouldn't have ever conceived that it was possible to go from writing about pregnancy and birth and spit up to making writing into a life and a living for myself without Heather. I wouldn't have learned that one even had the option of being that honest and that real and that true.

There was something about being a blogger in those early days. Something special that I can never quite put into words when I try to talk about it. Something i've mourned ever since the day Google Reader died and I really admitted the era was over. You said it in that paragraph above. In those days, we learned we were writers, and we learned how to write. It was always bigger than the minutia of our days, it was us learning to tell the truth about our lives. And she was the one who put the flag in the ground and claimed the space and made sure we all had a seat at the table.

Rest easy indeed.